Bird’s Eye View

Alana Hoare; Olubukola Bosede Osuntade; and Rumana Patel

Summary of Ethical Paradigms

Ethics refers to considerations about what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong.’ The eight lenses help leaders determine what is right and wrong from different perspectives. There is no hierarchy among the lenses (i.e., one is not better than the other); although, at times, people have been guilty of reinforcing one lens at the expense of another. Each lens on its own has strengths and drawbacks, leaving potential gaps in our peripheral vision. The aim is to combine multiple lenses to deepen our analysis of ethical dilemmas and become more thoughtful, reflective, and ethical leaders.

An advanced understanding of ethical theories allows leaders to better understand themselves and those around them and motivates them to consider the contextual factors and concerns relevant to a given circumstance. This can provide leaders with a more holistic understanding of phenomena (e.g., competing interests, power structures, and social and cultural factors) surrounding dilemmas. This also helps leaders become more attuned to the decision-making considerations and processes adopted by others and can facilitate collaboration across groups. In the next part of this book, you will apply the eight ethical paradigms to real-world ethical dilemmas.

St’at’imc Matriarchal Leadership Ethics

St’at’imc Matriarchal leadership ethics acknowledge the inherent rights of Indigenous women in making decisions regarding their community’s health, and preserving their culture, language, and connection to the Land. Leaders who follow this ethic empower youth by nurturing their strengths and enveloping them in the wisdom of the ancestors, Elders, and Land. This ethic is based on the belief that children are inherently good and that it is our duty to recognize and nurture their strengths. St’at’imc Matriarchal leadership ethics emphasize consensus-building, intergenerational knowledge transfer, cultural preservation, and prioritize Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination.

Ethic of Justice

The ethic of justice, which forms the structure binding Western society, is a decision-making paradigm that relies upon existing codes, laws, legislation, and policies to determine the appropriate course of action in each circumstance. It is a rule-based decision-making perspective. Leaders who follow this ethic value maintaining order in society through a fair and even application of universal standards. Uniformity and universal individual rights are highly valued. All individuals are treated the same and justice is distributed with exact similitude.

Ethic of Critique

The ethic of critique is antithetical to the ethic of justice and aims to dismantle the structures that bind society in the pursuit of more equitable outcomes. Leaders who follow this ethic believe that the ‘rule of law’ was created by those in power to maintain their power and to subjugate or oppress the powerless. Leaders aim to disrupt the status quo and advocate for the interests and needs of those underrepresented and underserved in education by critiquing, challenging, and changing the social structures and systems.

Ethic of Care

An ethic of care is also juxtaposed to an ethic of justice. The ethic of care emphasizes the significance of empathy, compassion, and responsiveness in directing moral conduct; it is a relational process focused on building connection and trust. Leaders who follow an ethic of care prioritize the well-being, dignity, and best interests of those whom they serve and are motivated to act. Care-based leadership requires much more than a feeling of caring for another; it requires leaders to challenge the status quo.

Ethic of Community

The ethic of community is underpinned by the belief that everyone is responsible for leadership. Anyone who cares about student success and what happens within post-secondary institutions recognizes that working toward social justice is a communal responsibility rather than that of a “heroic” leader with a vision. This ethical paradigm shifts the locus of moral agency to the community as a whole. Moral leadership is thus distributed and requires that all members of the community develop and practice interpersonal and group skills, such as working in teams, engaging in ongoing dialogue, and navigating evolving community discourse within an increasingly polarized society. In addition to being a communal affair, the ethic of community is processual, meaning that “community” is not a product nor tangible entity, but rather an ongoing set of processes led by educators and students committed to these processes. When community is defined as a process, it is based in relationships, which are dependent upon communication, reciprocity, respect, dialogue, and collaboration rather than a set of shared values.

Ethic of Self-Care

The ethic of self-care follows the ethic of critique; however, it is aimed inwardly at the self as the vehicle for disrupting and resisting dominant ideologies. It demands that leaders actively question and resist forms of power that operate through the regulation and normalization of individuals’ behaviors and identities by challenging how history and ‘truth’ are constituted and taught. To follow an ethic of self-care requires ongoing critical self-reflection on how you are governed by external forces, including how you may be influenced by societal expectations and institutional norms. This ethic is focused on developing oneself as more morally and ethically enlightened; it is not about dictating morality to others — it is anti-authoritarian in nature. It emphasizes the moral importance of self-nourishment and resilience, a perspective that is distinct in its focus compared to other ethics that may prioritize outward responsibilities over self-care.

Ethic of Discomfort

The ethic of discomfort follows the ethic of critique and self-care in a pursuit to disrupt and challenge dominant narratives and structures that perpetuate discriminatory, racist, and misogynist beliefs and practices. Leaders who adopt this approach challenge themselves and others to critically analyze their ideological values and assumptions. To do this may require that they feel pain and discomfort by experiencing discrimination and oppression firsthand, even if artificially, and to ‘walk in someone else’s’ shoes’ to build empathy and the ability to see things from another person’s point of view. The ethic of discomfort is different from other paradigms that may seek to mitigate discomfort.

Ethic of the Profession

The ethic of the profession is a multi-dimensional approach for decision-making that considers the ethics of justice, critique, and care alongside the leader’s personal and professional codes of ethics. The ethic of the profession places the best interests of the student at the centre of all ethical decision-making. From this perspective, educational leaders are called to provide a safe, respectful learning environment, and promote quality teaching. They are informed by an established set of professional standards and must be responsible stewards of institutional resources.

Framework for Ethical Decision-Making: “Bird’s Eye View”

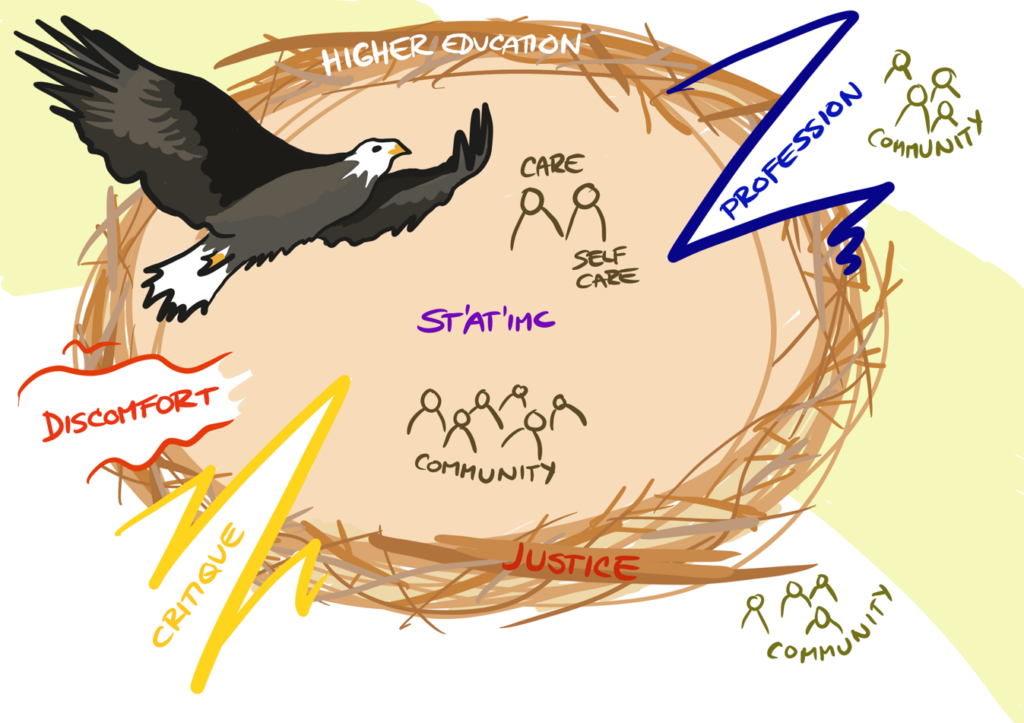

Drawing upon a vast body of literature, this book described eight ethical paradigms, as illustrated in figure below: St’at’imc Matriarchal leadership ethics, and the ethics of justice, critique, care, self-care, community, discomfort, and the profession. Leaders who are well-versed in multiple ethical paradigms and who consider different perspectives when making decisions are more reflective than reactive. Leaders with a strong grounding in the eight paradigms critically examine their prior assumptions, dispositions, and propensity towards certain decision-making approaches. They better understand themselves and are more effective at responding to ethical dilemmas in a culturally diverse environment.

Moral decision making starts first with the self by examining and interrogating our own beliefs and assumptions about what we consider right and wrong. It then expands outwards by considering those whose well-being we are responsible for (e.g., students) and then to the broader community and communities that we serve, respecting community values, supporting their priorities, language revitalization and land rights, and ensuring cultural sovereignty.

From there, we must attend to the laws, policies, and regulations of the educational profession and institutions in which we work, and the broader rules established where we live and those of our global collaborators. Once we are familiar with these laws, we must critically evaluate the ways in which they may cause harm, produce and reproduce iniquities, as well as the privileges they afford some while denying others.

Finally, we must be willing to sit within an uncomfortable reality that our actions may contribute to ableist, classist, racist, and, ultimately, systemic inequities. Educational leaders must be cognizant that every action taken or any decision made can have an immediate and long-lasting impact on the lives of people.

If we approach our work through a strengths-based lens (similar to that of matriarchal leadership) and eco-feminist views on the ethic of care:

- How might we balance the individual needs of students and advocate for more socially just educational systems?

- What might we learn from the land, our first teacher, about leadership?

- How might we incorporate eco-justice into our analysis of right and wrong?

Moral decision-making using a bird’s eye view starts from within and gradually expands outward, growing in focus and understanding. As we evolve and mature as leaders and as systems change and we gain more experience, decision-making must be considered as a never-ending cycle. Once we grasp the full picture, it is essential to revisit and re-evaluate our beliefs and assumptions continually and be open to humbly admitting mistakes and changing one’s course of action, when appropriate, particularly as new information arises or the impact of our actions has unintended results. As educational leaders, we have the capacity to be change agents, and the change begins within us.